by Michael J. Tuccinardi

Despite being the second-largest landmass on Earth, bounded by two oceans and two seas and having tens of thousands of miles of coastline, the African continent does not tend to be thought of in terms of its marine life. Africa’s east coast, however, boasts vast stretches of tropical coral reefs in the Western Indian Ocean, many of them teeming with reef fishes. And although relatively few aquarists know it, Kenya has been the site of a small-scale marine aquarium fishery supplying fishes, invertebrates, and—until recently—corals to the trade since the mid-1970s.

It’s no surprise that Kenya, with just 333 miles (535 km) of coastline, is far better known for its interior, which contains spectacular wildlife habitat and the famed Mount Kilimanjaro, and abuts Lake Victoria, one of the major hotbeds of freshwater cichlid diversity on the planet. Despite that, Kenya’s coast is unique in that much of it is enclosed by a massive barrier reef lying just a few miles offshore. This chain of barrier and fringing reefs extends for over 125 miles (200 km) along Kenya’s shores and southward into Tanzania. The northern Kenyan coast near Lamu has less coral cover due to the out-flowing fresh water of the Tana River, and north of that the coral reef zone is effectively bounded by an upwelling of cool water along the Somali coast, so the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts comprise a distinct coral reef ecoregion, according to J.E.N. Veron’s online database Corals of the World (www.coralsoftheworld.org). And while the country’s reefs suffered significant bleaching during the highly destructive El Niño Seasonal Oscillation of 1999 (and in subsequent events), overall the fringing and inshore reefs have recovered and survived intact, especially in and around the nearly 10 percent of Kenya’s offshore area that has been set aside as marine protected areas (MPAs).

Kenya’s offshore habitat is diverse, including nearly every type of tropical marine ecosystem, from vast mangrove swamps, seagrass beds, and shallow Acropora– and Porites-dominated fringing reefs to extensive deep water fields of soft corals and anemones. Over the course of my five-day visit, I was able to explore most of these habitat types and see many of the fish and invertebrate species that I had previously seen only behind glass. One of the first things that struck me about the underwater scenes off the Kenyan coast was the sheer volume of fishes present—huge shoals of Anthias were almost always in view along the reefs, and there were numerous large predatory fishes, like the schools of massive Southern Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) that I witnessed in the midst of a feeding frenzy just above one of the dive sites. Although it has a history of fishing and coastal resource use that extends back thousands of years, much of Kenya’s coast is sparsely populated, and there is relatively little in the way of industrial or large-scale fishing in most areas. This, coupled with the relatively healthy reefs, means that the fish assemblages along the coast have remained largely intact, despite some localized overfishing of food fish species.

The fish and invertebrate life found on Kenya’s reefs is extremely diverse, and while many of the commonly encountered species are found throughout much of the Indo-Pacific, East Africa boasts plenty of its own endemics. These unique species and distinctive populations— especially of reef fishes—have become staples of Kenya’s export trade, and over the course of my time there I was thoroughly impressed by the stunning array of fishes being collected in this undeniably exotic locale, although few are seen with any regularity in the U.S. aquarium hobby. Despite their relative scarcity in the trade, I couldn’t help but feel that many of them deserve more recognition. From an aquarium enthusiast’s standpoint, they certainly seem worth the extra effort necessary to seek them out—and not just for their uniqueness and suitability for any serious hobbyist who may have grown somewhat bored with the standard species seen in most marine and reef aquariums. I was struck by the obvious vitality and health of these fishes upon import, which was due to careful collecting methods—harmful and destructive techniques, such as cyanide fishing, are not utilized in the Kenyan aquarium trade—and short duration of transit from collection to export station.

For the next issue of CORAL I’ll examine the Kenyan marine fishery and provide a firsthand account of my time spent with the skilled divers who collect these fishes and invertebrates for their livelihoods, but for now I offer a detailed look at some of the country’s most impressive and unique fish exports, along with brief notes on their care in the aquarium.

LABRIDAE

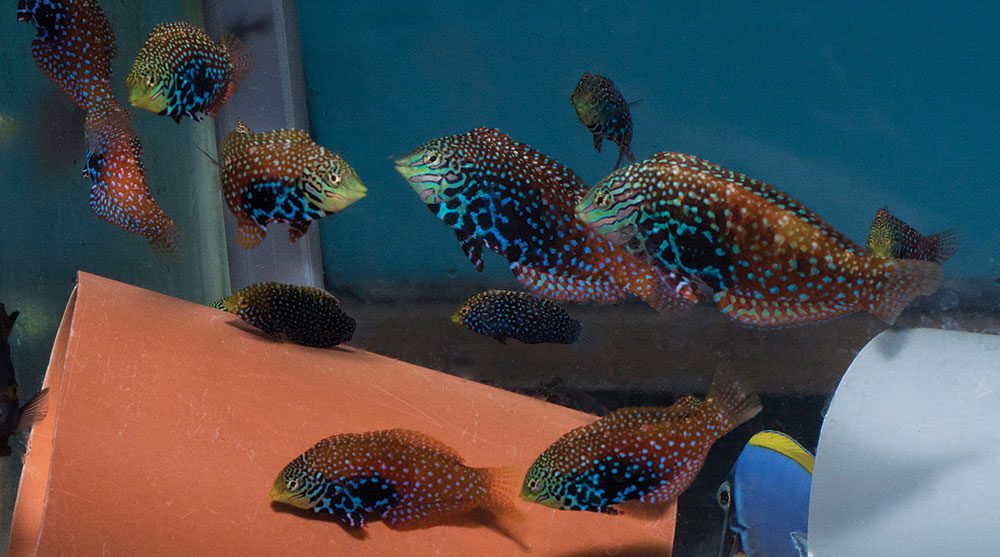

Blue Star Leopard Wrasse (Macropharyngodon bipartitus)

Probably the most beautifully marked of all the leopard wrasses, as members of this genus are commonly called, M. bipartitus is distributed widely throughout the Western Indian Ocean and is extremely abundant on most Kenyan reefs. Although wrasses of this genus have a somewhat deserved reputation for being delicate in the aquarium, much of this is likely due to poor handling and stress during and after collection and importation. A large, well-established aquarium, a substantial sand bed, and ample feedings of varied, high-quality foods appear to be the keys to keeping these somewhat fragile beauties thriving in captivity.

Radiant Wrasse (Halichoeres iridis)

A fish that certainly lives up to its name, the Radiant Wrasse is another Western Indian Ocean fish found in large numbers off the East African coast. Like most of its congeners, it requires a sand bed to sleep in and, while shy at first, generally adopts the gregarious behavior typical for this genus. Some reports indicate challenges with recently imported specimens, which I would probably attribute to transport stress or malnutrition. Most freshly collected fishes are active and enthusiastic eaters.

Yellowtail Tamarin Wrasse (Anampses meleagrides)

Although it is found throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific, this beautifully marked wrasse has long been considered a challenge to keep successfully. Specimens from Kenya, which do not usually suffer from extended time in transit before reaching an exporter, are likely to fare far better in the aquarium, which is why this species remains a popular export from the country.

Yellow-Breasted Wrasse (Anampses twistii)

Like other species of this delicate genus, this wrasse tends to fare poorly when handled roughly or subjected to poor conditions before and during export. Much like the leopard wrasses, they need ample sand beds and large, well-established aquariums to thrive.

Bicolor Cleaner Wrasse (Labroides bicolor)

Without a doubt an experts-only fish, this species should be kept in a large aquarium under the care of a highly experienced aquarist. Carefully collected specimens that haven’t begun wasting away due to lack of food—such as most specimens exported from Kenya—are far more likely to adapt and thrive in an aquarium.

Candycane Wrasse (Hologymnosus doliatus)

This is another commonly encountered denizen of Kenyan reefs. The attractively marked juveniles of this species tend to form loose schools as they hunt for small invertebrates. Relatively hardy in aquariums, they grow to a hefty 12+ inches (30 cm) as adults and so are only suited for large aquariums.

POMACANTHIDAE

Goldtail or Chrysurus Angel (Pomacanthus chrysurus)

This large, attractive angelfish is found only along the east coast of Africa and is among the most sought-after Kenyan exports. Although occasionally encountered on the reef, it tends to be more common in rocky and algae-dominated habitats on the North Coast.

Flameback Pygmy Angel (Centropyge acanthops)

Although remarkably similar to Centropyge aurantonotus, which, oddly enough, is found across the globe in the Southern Caribbean, C. acanthops is endemic to East Africa and sports a more vibrant orange coloration. On the reef, this fish tends to stay close to rock or coral overhangs and makes a colorful, if somewhat shy, aquarium resident.

POMACENTRIDAE

Allard’s Clownfish (Amphiprion allardi)

A beautiful, rather delicate East African species in the A. clarkii complex, A. allardi is typically found inhabiting Carpet Anemones (Stichodactyla sp.) or Ritteri Anemones (Heteractis magnifica). Although it has been bred in captivity, it is not commonly commercially available except as a wild-collected specimen from Kenya.

Vanderbilt’s Chromis (Chromis vanderbilti)

A widespread species that, unfortunately, is rarely seen in the hobby, this small-growing Chromis is both hardy and peaceful. Although not prone to forming tight schools like some of their congeners, they make attractive additions to a reef tank and tend to stick close to branching coral heads.

ACANTHURIDAE

Yellow Belly Hippo or Regal Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus)* *distinct population

Although the Blue, Regal, Palette, or Hippo Tang is among the most well-known and immediately recognizable of all reef fishes, relatively few people are familiar with the fact that there is a distinct population of this fish known from East African waters. These fish, in contrast to the uniform blue they display throughout the rest of their range, sport a pale yellow belly that develops further as they grow. Beyond this unique color pattern, which should interest any aquarium-keeper looking for something out of the ordinary, these fish are typically collected and held under far better conditions than Indonesian specimens, so they tend to acclimate to aquarium life without the health issues that often plague this species.

SCORPAENIDAE

Gumdrop Coral Croucher (Caracanthus madagascariensis)

This bizarre and minuscule member of the scorpionfish family is extremely similar in behavior to the well-known clown gobies of the genus Gobiodon, inhabiting coral heads almost exclusively in the wild. Technically venomous, these strange little fish adapt relatively well to aquarium life and would make a fascinating centerpiece for a nano reef.

CHAETODONTIDAE

Black Pyramid or Zoster Butterfly (Hemitaurichthys zoster)

This darker, Indian Ocean cousin to the more well-known Yellow Pyramid Butterfly (H. polylepis) is found in large aggregations just offshore along most of the Kenyan coast. This species is generally considered one of the more reef-safe species of butterfly.

The smoke from a smoldering cooking fire filled the small room and lingered just above the packed-earth floor. I was in the village’s only open “restaurant,” along with a few locals, who were sitting across from me on a rough-hewn wooden bench, quietly finishing an early breakfast. The familiar sounds of early morning in the developing world drifted in through the open door and windows—a rooster crowing apathetically, the far-off drone of a motorbike, and a pack of semi-feral dogs barking just outside. The proprietor of this little restaurant—an outgoing and rail-thin man in his early 60’s—leaned over to pass me my coffee and asked what brought me out to this somewhat remote spot. When I replied “aquarium fishes,” he responded with the bemused, slightly quizzical look I’ve come to expect from that answer. “We have those here?” he asked. “In Kenya?”

Many people, even longtime hobbyists, might ask the same thing. Kenya’s coastline, bordering the far western edge of the Indian Ocean, has been the site of a small but vibrant aquarium fishery for decades. Like many of the small-scale collection locales spread out across the world’s tropical oceans, Kenya’s marine aquarium fishery is relatively unknown and remains poorly studied. But the fishes that make their way into the United States and other import hubs across the world—several of which have populated my own personal aquariums—have held an enduring fascination for me, and for that reason I found myself traveling across the Indian Ocean from Colombo, Sri Lanka, to Mombasa to get a firsthand look at Kenya’s marine aquarium trade.

Arranging to see aquarium fish collectors in action, whether in the South China Sea or the Amazon Basin, is rarely a simple task. Success depends on complex, often last-minute travel plans, good weather, and no small amount of luck. On this trip, however, I had few obstacles to contend with, as I had help from one of the country’s largest fish exporters, Kenya Marine Center. The company’s founder, Jochen, had organized transportation and allowed me to accompany his divers and collectors along the coast for the duration of my visit.

And so, in the tiny village of Gazi, nestled against the mangrove forests along Kenya’s South Coast, I waited for the team of divers to meet me and begin the day. Another watery instant coffee later, they began to trickle in. One of the youngest, having had the good fortune to collect a rare Gem Tang a few days before, was clearly suffering from the after-effects of a long night of celebrating his valuable find. One of them beckoned me to the door, and I followed them out to a wide, sandy beach where the boat was waiting.

FISHERY BACKGROUND: GEOGRAPHY

Over the next few days, I went out with dive teams along the coast to observe fish and invertebrate collection in action, traveling back each afternoon, along with the day’s catch, to their holding facility. Due to the relatively short coastline, most of Kenya’s aquarium trade is concentrated in a few collecting locations, most of which are only a few hours’ drive from export facilities clustered near the international airport in Mombasa.

The sprawling city of Mombasa, which has a population of over one million, is actually an island nestled into the southern edge of the Kenyan coast, less than 60 miles from the border with Tanzania. Its history stretches back over 1,000 years; it has been a Portuguese trading post, a British Protectorate, and a vassal state of the Sultanate of Oman. Today, it is a victim of the uneven pace of Africa’s urban development, and the dense population, heavy ship traffic in and around the port, and largely unregulated sprawl have heavily impacted the waters surrounding the city. Fortunately, the damage to inshore reefs has been localized, and it only takes a short time to reach intact, richly populated reefs just beyond the coast’s pristine beaches. A remarkable percentage of Kenya’s coastline is relatively healthy fringing reef, and the South Coast is home to the most vibrant of these.

This, combined with the proximity and easy road access to export facilities, is why the South Coast remains the favored region for ornamental fish collection in Kenya—and why I found myself on a traditional wooden boat heading out toward the extensive barrier reef outside Gazi, close to a kilometer from shore. The divers and boat crew, at first clearly a bit on edge having a foreigner in their midst, had relaxed and were now preparing for the dive. The majority of the collecting in Kenya is done by fairly well-organized and well-equipped dive teams using SCUBA gear. The reefs with the densest populations of desirable aquarium fishes tend to be around 30 to 60 feet (10–20 m) down, and although some areas had obviously been damaged in earlier bleaching events, these reefs were, for the most part, in good condition. The fish diversity was also remarkable; small schools of Powder Blue Tangs (Acanthurus leucosternon) were visible in every direction, and huge mixed-species groups of wrasses foraged close to the coral heads along the bottom.

NET-FISHING: AN ACQUIRED SKILL

Divers use barrier nets to collect fishes, deftly laying out the net in a semicircle on the seafloor and using it to corral the desired fishes into a smaller hand net before transferring them into standard plastic fish bags tied to their belts. Aquarium fish collecting in Kenya is, as in several other small-scale aquarium fisheries, a skilled trade requiring years of training and practice, and most of the divers I met had been collecting fishes as their primary source of income for more than five years—and some far longer. As always, I was amazed at the level of local ecological knowledge displayed by these collectors, who (when asked) can usually rattle off detailed information about the seasons for certain fishes at certain sizes, the influence of the tides and lunar cycles on fish abundance, and even what sites offer the best collecting at various times throughout the year. Each diver’s single tank of air is the major constraint on collecting, and they waste no time once in the water, scouting on their descent for groups of fishes to target and fanning out nets as soon as they reach the bottom. In a careful but hurried process, the divers spread out across the reef and pursue their targeted species, which vary according to what the exporter demands.

Although each exporter (there are three or four currently operating in the country) likely uses different methods with his own divers, the fact that Kenya’s fishes go directly from diver to exporter, typically in the same day, is hugely advantageous in terms of both communication and minimizing over-collection. Each dive team I spent time with went out with a rough list of what was needed, and for abundant or easy-to-collect fishes like damsels there was a quota in place—anything above that number would be paid for, but at a much lower price. During the 40- to 45-minute dives, the collectors gradually fill their belts with bags of fishes, from groups of Blue Star Leopard Wrasses (Macropharyngodon bipartitus) to reverse harems of the widely abundant Allard’s Clownfish (Amphiprion allardi), with the occasional larger bag reserved for single specimens of large angels like the Emperor (Pomacanthus imperator) or the sought-after Goldtail Angelfish (P. chrysurus). Above the surface, the boat crew times the dive and keeps close watch on the makeshift buoys, waiting for divers to surface.

Once the divers begin to surface, the crew springs into action and a flurry of activity ensues as the collectors, bags of freshly captured fishes in hand, haul themselves up and over the gunwales of the boat. Oxygen tanks are brought out and the divers and crew begin sorting the catch, re-bagging and changing water when necessary, before inflating the bags with pure oxygen. Each diver’s catch is placed in a separate pile in a shaded spot or under a tarp, and soon the divers begin preparing to repeat the process.

SNORKEL COLLECTING

On a typical trip, the collectors make two dives, each lasting around 45 minutes, with a break in between while the boat makes its way to the second site. By the time the hot equatorial sun is high overhead—just around noon—the second dive has usually been completed and it is time to head back to shore. En route, the divers work quickly to re-bag most of their fishes once more, this time sorting them by size and species, performing additional water changes (big grazers like tangs and angels can make quite a mess in a short time) and, finally, marking the bags with scraps of paper on which they’ve written their initials—a simple yet effective system to ensure that each diver gets paid for the fishes he has caught.

Although teams of divers like the ones I traveled with are responsible for the lion’s share of aquarium fishes exported from Kenya, a significant percentage of snorkel-based collection occurs in the shallow inshore areas as well. On my last day in the country, I was able to accompany a group of snorkel collectors while they collected fishes and invertebrates. In contrast to the deeper coral reef habitat, this collecting site was primarily a vast seagrass flat, punctuated by rocky outcroppings with moderate coral coverage. Despite being far from “typical” reef habitat, these seagrass flats were no less productive in terms of fish diversity; dense schools of damsels, small surgeon fishes, and butterflies were easy to spot and approach. Because it requires far less skill and training, snorkel collecting is often an entry-level position for younger fishermen looking for work in the aquarium trade. Over time, snorkel collectors who prove adept at collecting and produce fishes in reliable numbers are offered the opportunity to train as divers, which comes with a substantial increase in earning potential.

Like many marine aquarium fisheries, the commercial trade in Kenya began in the early 1970s (Okemwa et al. 2005), at a time when the combination of improved air transportation and early success keeping marine aquariums drove some enterprising members of the industry to look beyond the established export points in the Philippines and Hawaii. Kenya’s reefs, which boast a wide variety of endemic, aquarium-suitable species (for more information on these, see Part I of this feature in the previous issue), made for an attractive, if logistically challenging target for the growing trade. Although there is no written history of the trade in Kenya, multiple sources relayed to me that one or more German expats began the first collection and export operation in the country. For many years, Kenyan fishes were sought by aficionados of the uncommon, but were only intermittently available. During the 1990s and into the 2000s, Kenya’s marine aquarium industry saw increased involvement by a few major importers in the US and Europe and developed significantly, and once-sporadic shipments became far more regular.

MONITORING ARTISANAL FISHERIES

For a time, even corals were exported and the main collection point, Shimoni, on the Southern Coast, became something of a well-known name among importers and members of the trade. To this day, the Kenya Tree Coral (Capnella sp.)—which, if I recall correctly, was the first coral I ever bought—remains a staple of the hobby, although its namesake country no longer allows the collection or export of any coral species. Today, a handful of exporters continue to ship fishes and invertebrates regularly from Mombasa International Airport, primarily to Europe and the United States. Although the “boom years” of the business have probably passed, aquarium fish collection remains an important business for those involved.

Like nearly all small-scale aquarium fisheries, Kenya’s has been poorly studied and would be considered data-deficient by nearly any standard. The country’s artisanal food fisheries, however, are fairly well-documented in the scientific literature, and many of its reefs have been monitored and studied for decades. This allows at least some insight into the fishery on an ecosystem level and, combined with what limited data does exist on aquarium fish collection, helps paint a picture of where the aquarium trade in this country, and the ecosystems that sustain it, stand today. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the degraded state of coral reefs worldwide, this is a bit of a mixed bag. Generally speaking, Kenya’s food fish trade has remained small-scale, and they have never had a massive industrialized fishing fleet like those seen in other Indian Ocean countries. This has almost certainly helped protect reef habitat from widespread destruction due to trawling and rampant overfishing, but even small-scale fisheries can have a significant impact. Research indicates that after a peak in the late 1970s, overall catch per unit effort (CpUE, an important indicator of fishery health) has declined for all types of artisanal fishing along the coast (Samoilys et al. 2016). While this decline has not been nearly as precipitous as in some other regions, it is still indicative of trouble ahead for many of the important food fish families.

Kenya’s coral reefs, while still considered to be in relatively good health, have suffered a great deal in recent years. Major bleaching events in 1997–98 and 2007–08 caused significant loss of coral cover in many areas, although periods of recovery helped regain some of what was lost. Kenya also has an extensive range of marine protected areas along its coast, covering over 10 percent of its offshore area in total. Although enforcement of these areas (which includes strict no-take national parks) has varied in the past, a number of studies indicate strong recovery of fish and coral abundance and species diversity both in and around these areas. As is often the case, very little research has been done into the specific impacts of the ornamental trade, but given its small, localized nature and relatively low volume of locally abundant species, it is likely that the negative effects have been limited. Divers I spoke to, although keenly aware of lower numbers of food fish species in their collecting sites, generally did not see this decline extending to the aquarium species they targeted.

In an age of increasing concern about unsustainable sourcing of all manner of consumer products and widespread global decline of coral reefs, it remains surprisingly difficult to make purchasing choices for our reef aquariums that don’t contribute to either. Even defining what is and what is not sustainable with regard to the trade and hobby remains a fraught discussion, especially given the lack of research into most marine aquarium fisheries. In Kenya’s case, however, there are, at the very least, a few indicators that this fishery is among the better options for sourcing aquarium fishes and invertebrates. First and foremost, cyanide use and other destructive collecting practices are unknown in the country’s reefs. Also of great importance is the relatively direct route that freshly collected fishes take from reefs to export facilities just a few hours away. This dramatically improves survival rates and prevents the over-collection that results from poor communication between collector and buyer or the need to offset the high mortality rates associated with long, complex supply chains. Finally, Kenya’s extensive marine protected areas offer an important reservoir for species diversity and likely create what is known as the “spillover effect,” in which stocks of fishes and invertebrates in the surrounding areas are augmented. In the absence of hard data, it is difficult to support claims either for or against the sustainability of aquarium fisheries like Kenya’s, but these small-scale fisheries increasingly seem to be a better sourcing option for hobbyists looking to minimize the impact their aquariums have on wild reefs.

Image Credits:

Images by Michael J. Tuccinardi unless otherwise noted.